Donald L Barlett and James B. Steele are not just one of journalism’s most iconic duos in recent history but a unique partnership that has spanned over 40 years. They’ve worked together at The Philadelphia Inquirer, Vanity Fair, and Time and are the only journalism duo in history to have won two Pulitzer Prizes.

The two men first met in 1970 at

The Philadelphia Inquirer after each had successful careers at other papers

throughout the years. They hit it off immediately, and their brand of

investigative journalism quickly became a staple of the industry.

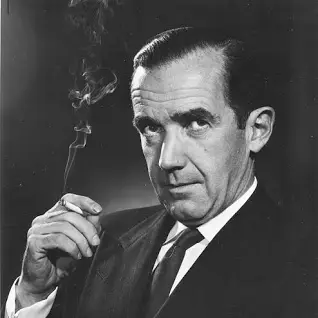

| Donald L Barlett |

Bob Woodward, fellow investigative

journalist and associate editor at the Washington Post, described them as an

institution. “They have kind of perfected a method of doing their work, and I

have the highest regard for it. Systematic, comprehensive - they take a long

time, and they don't mind saying what their conclusions are."

| James B. Steele |

Barlett and Steele’s first Pulitzer

was for a series they published, “Auditing the Internal Revenue Service,” which

exposed the unequal application of federal tax laws. Their second was for their

coverage of the Tax Reform Act of 1986. They were watchdogs over the House of

Representatives, calling out the addendums consistently slipped into the act. They

kept the government accountable, telling the public exactly what they were doing

and how they did it.

They are also known for popularizing

technology in violent crime reporting. They used a computer to analyze over

1,000 cases of violent crime, finding patterns and other vital data in the biggest

computer-assisted journalism venture of the time.

After 26 years at the Inquirer,

Barlett and Steele left to become editors-at-large for Time Magazine. Their work earned them two National Magazine Awards. The awarded series were "What Corporate Welfare Costs You" and "Big Money and Politics: Who Gets Hurt." Full records of their most notable stories are available on their website.

|

| Title & Opening |

From 2006 to 2016, the pair acted

as editors for Vanity Fair, continuing to follow the difficult stories

that won them their reputations. They covered the disappearance of billions of

dollars in cash the U.S. airlifted to Baghdad at the outset of the Iraqi war, the

strong-arm tactics of Monsanto against America's farmers, and many other

notable events.

Today, both men have retired from reporting.

Steele lectures at universities nationwide, and Barlett lives at home with his

family. They are journalism heroes in the truest sense, and their impact on the

industry will be remembered.